Liam Noble writes: I never met Carla Bley, but in many ways her music has been a constant companion over the years. I love the way her music teases the edges of the mainstream whilst preserving melody at its centre. For me, it always seemed it was simply, and only, about the notes, a characteristic she shares with the music of her long-time partner and collaborator Steve Swallow. She found a way to be acerbic and witty without losing the warmth, and somehow stayed unmistakably herself as the music went through radical changes. I think that’s down to the notes, it’s down to respecting them as living things. How they move and why.

My first introduction to her music was “Carla Bley: Live”, and I still remember the opening track, “Blunt Object”. From a kind of faux-horror movie opening to the sudden punch of the groove, she seemed to make music out of tiny fragments expertly assembled. I loved the economy of it, and the insistent repetition of that bass line, familiar yet skewed somehow. Everything is clear, direct and to the point, there’s a simplicity infused with a healthy dose of madness. “The Lord Is Listening To Ya, Hallelujah” reads like a Frank Zappa title, and whilst Gary Valente’s tone sounds like something about to explode, and the audience are clearly chuckling in places, you can’t ignore the sheer beauty of the harmonic twists. There’s a slight confusion of the senses somehow, I don’t know of it’s funny or sad, whether to be moved or to laugh out loud. I’d seen that in one other musician: Thelonious Monk. Her Hammond solo, following Valente’s, is so simple it’s almost not there but it’s utterly beautiful too.

Going back a bit, her pieces for Paul Bley, her then husband, are little gnarly expanding bombs of musical information, like Ornette with pianism. “Jesus Maria”, one of her earliest tunes played by the Giuffre/Bley/Swallow trio in 1961, seems to invent its own emotion, complicated and bitonal, simple in its utterance. “Vashkar”, “King Korn”, “Floater”, “And Now, The Queen”…all masterpieces of concentration, little ginger shots of sound that inspired players like Paul Bley, John Gilmore, Paul Motian and Gary Peacock, amongst many others, to make some of their best work. “Jesus Maria” returns on her 1979 album “Musique Mechanique”, a little more cranky and features Eugene Chadbourne speaking through a walkie talkie. But by this stage, she had already been through a revolution in sound sparked by The Beatles that had led her to her three album jazz opera, “Escalator Over The Hill”. (I’ve only just started to digest this extraordinary piece.) Things had changed.

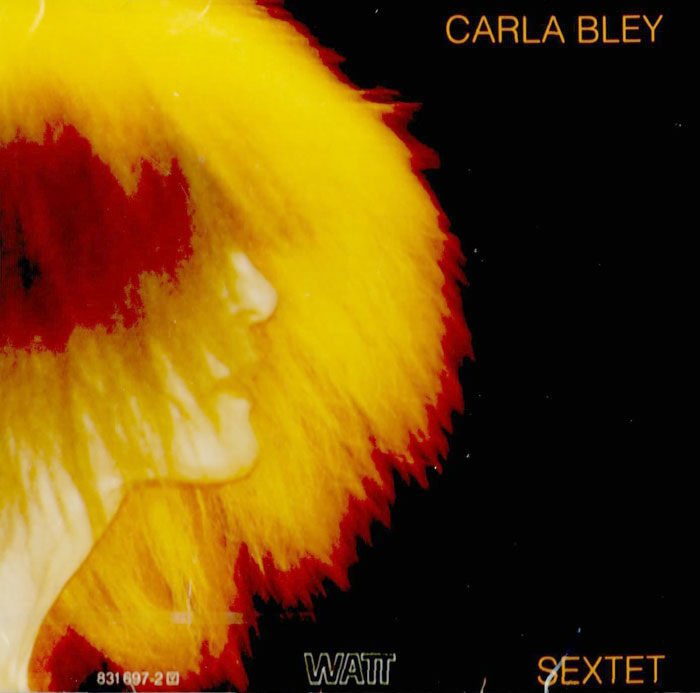

One of my favourite albums is “Sextet”, an almost impossibly polished gem from the mid-eighties that washes right over you if you let it, but once you get into the detail you can’t unhear it. A tune like ”Lawns” circles around a single place in so many ways, and the tiny differences between them are its subject. “Healing Power” could be straight off an Al Green record, and “The Girl Who Cried Champagne” is like some kind of strange exercise in chord rotations that never come out where you want them to. Along with Steve Swallow’s albums of that time, these are records that, for me, show the deepest respect for, and understanding of, simple harmonic movement. It’s like she’s making us look again at everything we took for granted, stripping the music back to its essentials rather than piling on layers of complexity. In such a low friction environment, the smallest change in phrase length, the slightest dissonance, jumps out in new ways. The band are smooth and sparkly, no horns.

But Bley’s music changed again, moving back towards large ensembles. On Charlie Haden’s “Dreamkeeper”, she provides a series of choral interludes that take my breath away every time. “The National Anthem” on “Looking For America”, a2003 big band album, makes you sit through a good few minutes of funk, including a typically pithy piano solo, before the National Anthem emerges half way through its own melody, only to be interrupted again by an arrangement of Bley’s old tune “Flags” and some good old fashioned military snare work. The effect is a kind of Ives-ian comic montage, and seems to tie a lot of her previous preoccupations together. I love the way she makes us wait for that tune!

But my favourite stuff are her duos with Swallow, “Duets”, “Go Together” and “Are We There Yet”. Tunes like “Sing Me Softly Of The Blues”, “Baby Baby” and “Fleur Carnivore”, with Carla’s stoical playing to the fore, sound better than ever. She plays the piano exactly the way I love to hear it, spare and close. Steve Swallow is perhaps my favourite living accompanist, and the music moves haltingly, as if finding its own way, writing itself. The bond between them is touchingly clear throughout. It’s these records that I went to after I heard the news of Carla Bley’s passing. Somehow it’s here, where she is at her most exposed, accompanied only by her closest musical and personal friend, that I feel the gap she has left most profoundly.

Born (as Lovella May Borg), Oakland, California, 11 May, 1936. Died Willow, New York, 17 October 2023

That’s a lovely summing-up of Carla Bley and her music, one of the best things I’ve read in the week since she died. Thank you, Liam Noble.

Great tribute to a wonderful artist, thanks.